When Scaffolds Become Ceilings

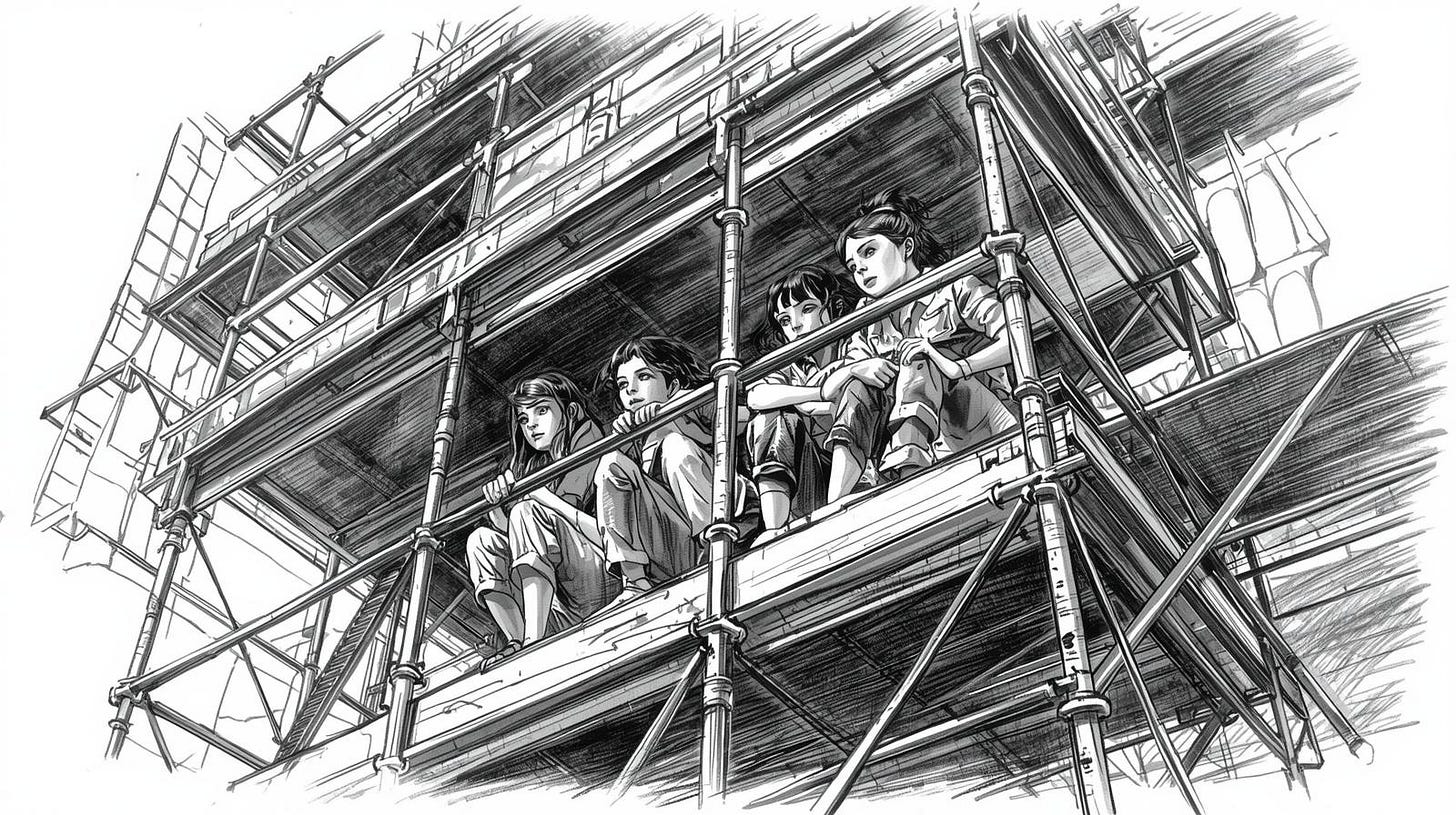

What if the very scaffolds we design to support learning are the same ones that prevent it?

I’ve been sitting with this lately, both in classrooms and as a parent. Scaffolds are meant to lift, to steady, to protect.

But what happens when they stay in place too long?

Do they start to hold us back instead?

Ladders or Ceilings?

In theory, scaffolds are elegant: temporary structures that allow learners to reach higher than they could alone. Once stability comes, the scaffold fades away.

But in schools — and in life — scaffolds don’t always behave so neatly. They linger. They multiply. They become routines.

“They stop being ladders and start becoming ceilings.”

From Disrupting to Driving

Amy Berry (2022) helps me think this through. She frames engagement as a continuum: disrupting → participating → driving.

Disrupting: pushing back, resisting, avoiding.

Participating: doing what is asked, willingly enough, but within the boundaries set by others.

Driving: taking ownership, shaping direction, self-regulating, pushing learning further than the adult imagined.

So often, I see scaffolds keeping children in that middle stage. They’re busy. They’re compliant. They’re participating. But they’re not yet driving.

And that leaves me asking: are we preparing them to act for the sake of learning itself — or simply to comply with the system that rewards participation?

What the Research Tells Us

The theory on scaffolding is deep and well-established.

Vygotsky (1978) placed scaffolds at the heart of the zone of proximal development.

Wood, Bruner, and Ross (1976) described them as temporary supports that enable a learner to succeed where they could not succeed alone.

van de Pol, Volman, and Beishuizen (2010) showed that scaffolds only work if they fade.

Hammond and Gibbons (2005) reminded us that scaffolding through language can open thinking, but over-direction suffocates it.

Sweller (1988) demonstrated how scaffolds reduce cognitive load for novices, but can actually hinder advanced learners if they linger.

Puntambekar and Hübscher (2005) argued that scaffolds must prepare learners for transfer, not just task completion.

The message across decades of research is consistent: scaffolds matter most when they disappear.

What We Mean by Scaffolding

A scaffold is a temporary structure used to support workers and materials when building, repairing, or cleaning a building.

In teaching, a scaffold is a temporary support given to learners to help them accomplish a task or understand a concept they couldn’t manage on their own. The teacher provides guidance, prompts, tools, or structure.

As learners gain confidence and skill, the support is gradually removed — just like scaffolding is taken down once a building stands on its own.

Scaffold = temporary support that helps you reach higher until you can do it independently.

But: what happens if it never gets removed?

If scaffolds never come down in learning…

Dependence develops: Pupils rely on prompts, sentence starters, visuals, or teacher cues and don’t attempt tasks independently.

Limited transfer: They can perform with the scaffold in place, but struggle when asked to apply the skill in a new context.

Ceiling on growth: The scaffold becomes a permanent crutch, stopping learners from stretching beyond guided steps.

False sense of mastery: Work may look strong, but it reflects the support system, not the learner’s own capability.

What’s supposed to happen

Scaffolds are faded gradually as competence grows. Responsibility shifts from teacher → shared → pupil. Learners internalise strategies so they can plan, monitor, and evaluate their own work without external support.

An Analogy: Training Wheels

I’ve watched my own children learn to ride bikes with training wheels. At first, the extra wheels are essential. They give balance, reduce fear, and allow the rider to focus on pedalling.

But training wheels are not neutral. They change the way the bike moves. They stop the natural lean into corners, the subtle shifts of balance, the control that only comes with risk.

And here’s the irony: if the wheels stay on too long, the rider can cycle further — but never really learn to ride.

“They participate, but they do not drive.”

That image haunts me when I think about scaffolds in classrooms. What looks like steady progress can mask a deeper dependence.

The Adult Dilemma

Here is the tension I wrestle with:

How do we know when to remove the scaffold?

As adults — teachers, leaders, parents — we like smoothness. Quiet classrooms, finished tasks, tidy transitions. We step in quickly to keep things “on track.” But efficiency can come at a cost.

If scaffolds are taken away too soon, learners falter. If they’re left too long, independence suffocates. How do we know when the timing is right? How do we release the slack, but not abandon?

And most of all: how can we be sure that when we remove the supervision, the set tasks, what remains is not just habit, but values? The drive to learn for the sake of it. The choice to behave in ways that are respectful, safe, and contributing — not because an adult is watching, but because it matters.

This keeps me up at night.

Scaffolds On, Scaffolds Off

In classrooms, this dilemma is perhaps most visible in the tension between direct instruction and an inductive approach to learning.

Direct instruction is often heavily scaffolded. The teacher holds the structure, carefully sequencing each step, controlling the pace, monitoring behaviour, and ensuring that everyone is moving together. It is efficient. It keeps the room calm. Pupils know what is expected.

But an inductive approach feels different. This is where the scaffolds come off, but are not absent. Pupils are expected to do the thinking, to make the connections, to wrestle with the ambiguity until the fog lifts.

“Louder, messier, a buzz of talk… the sound of learning happening on their own terms.”

I call these the “scaffolds-off moments.” They are not always comfortable, and they are not always tidy. But they are incredibly necessary. Without them, children remain participants. With them, they begin to drive.

Not all day, perhaps. Structure is still important. But increasingly, more and more, pupils need to live in that space where the scaffolds are loosened.

Practising the Choices

And here’s the critical point: when pupils are asked to drive their learning, it isn’t just about the task, it’s about the behaviours they choose.

When scaffolds come off, pupils are responsible for how they learn: how they collaborate, how they manage their time, how they persevere when it gets hard, and how they express their thinking.

This is where the IB Learner Profile attributes and the Approaches to Learning (ATL) skills come alive.

Open-mindedness, balance, risk-taking, reflection — not abstract ideals, but real dispositions guiding behaviour when adults step back.

Self-management, communication, research, thinking, and social skills — the muscles that must be flexed when pupils drive their own learning.

But these do not develop by osmosis. They develop by practice. Which means we have to create scaffolds-off moments on purpose, giving children opportunities to test these skills in safe but challenging contexts.

It will be messy. Sometimes they will choose poorly. But if we never let them practice, the Learner Profile and ATLs remain words on a poster rather than lived habits.

Beyond the Classroom

This isn’t only about children. Schools scaffold teachers, too.

We provide templates, scripts, PPTs and pre-packaged systems. We call it support — and sometimes it is. But sometimes it becomes a constraint. Too much scaffolding of teachers erodes the very agency we want them to model for pupils.

As leaders, we talk about innovation, but our processes often reward compliance. We ask pupils to drive their learning, while giving adults very little space to drive their teaching.

Ron Heifetz, Alexander Grashow, and Marty Linsky (2009) make a useful distinction: technical fixes (scaffolds, structures) are important, but adaptive work — navigating ambiguity, wrestling with values — is where real growth happens.

“We risk building ceilings over both teachers and pupils.”

A Parenting Parallel

As a parent, this question feels even sharper.

When I loosen my supervision, when I stop setting every boundary, how do I know my children will choose well? I can only hope that the values I’ve tried to instil — kindness, safety, contribution — will hold when no one is watching.

It’s the same with pupils. We scaffold behaviour, routines, and learning in the hope that when the supports are lifted, they won’t just collapse into disruption, but step into driving.

But this is a fragile hope, not a guarantee. And perhaps that’s the point. There’s no formula for the “right moment” to remove scaffolds. It is judgment, risk, and trust — and it will always be a complex web.

A Tension Worth Holding

None of this is straightforward. Scaffolds are necessary. Without them, learning falters. With them, left in place too long, agency suffocates.

So perhaps the work is not in perfecting scaffolds but in perfecting our judgment about when to remove them. To trust that what remains will be enough. To accept the wobble, the stumble, the uncertainty, because that is where driving begins.

“Agency — for pupils, for teachers, for our own children — rarely grows in the comfort of supports that never fade.”

That is the tension worth holding.

References

Berry, A. (2022). Reimagining student engagement: From disrupting to driving. Corwin Press.

Fredricks, J.A., Blumenfeld, P.C., & Paris, A.H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109.

Hammond, J., & Gibbons, P. (2005). Putting scaffolding to work: The contribution of scaffolding in articulating ESL education. Prospect, 20(1), 6–30.

Heifetz, R., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009). The Practice of Adaptive Leadership. Harvard Business Press.

Puntambekar, S., & Hübscher, R. (2005). Tools for scaffolding students in a complex learning environment. Educational Psychologist, 40(1), 1–12.

Skinner, E.A., & Pitzer, J. (2012). Developmental dynamics of engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In S. Christenson et al. (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Springer.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285.

van de Pol, J., Volman, M., & Beishuizen, J. (2010). Scaffolding in teacher–student interaction: A decade of research. Educational Psychology Review, 22(3), 271–296.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in Society. Harvard University Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100.