Professional Learning Communities: Beyond Buzzwords to Real Impact

Building Interdependency, Inquiry, and Impact for the Future of Learning

We all know what it feels like to work in an effective team.

That flow of understanding your role, recognising each other’s value, knowing you can depend on one another. There is confidence that expertise is present in the room to deliver the work to a high standard. And the deep satisfaction of seeing how, collectively, you’ve made a difference.

So… enter the Professional Learning Community (PLC). The question is: how do school leaders set this up successfully?

- What needs to be communicated?

- What needs to be systematically supported?

- What are the essential elements?

In this post, I draw from my own experiences and stand on the shoulders of giants who have spent countless hours researching and developing frameworks to give schools mental models for nurturing such environments.

My encouragement to you is this: don’t get caught in the weeds. Yes, there are details and frameworks, but the essence is simple: progressive collaborative inquiry is the heart of interdependent work that makes a difference to learning, for both teachers and pupils.

So as you read, come back to that intuition: remember the feeling of what it is like to work in an effective team. Trust in that.

Progressive collaborative inquiry is the heart of interdependent work.

What Do I Mean by Progressive Collaborative Inquiry?

At its heart, collaborative inquiry is when a group of teachers work together through a disciplined cycle:

- identify a problem of practice,

- frame a question,

- trial strategies in classrooms,

- gather evidence,

- reflect and adapt.

The “collaborative” part means the thinking, action, and reflection are done collectively, not alone.

But when I use the phrase progressive collaborative inquiry, I’m signalling something more. It’s not just about completing a single cycle well; it’s about building momentum over time. Each round of inquiry should deepen, refine, and extend both teacher practice and student learning. It’s a stance, not just a method:

- iterative progression → each inquiry cycle grows sharper and more impactful,

- forward-looking orientation → the goal isn’t only solving today’s gap, but growing teacher capacity and shaping future practice.

In other words:

- Collaborative inquiry is the method.

- Progressive collaborative inquiry is the culture — a habit of professional life where every cycle builds on the last, creating continuous improvement.

Example: a Year 5 writing team co-designs a shared mini-lesson, trials it, and reviews the impact. That’s collaborative inquiry. When that team then comes back to refine its process, connects to wider school goals, and steadily embeds inquiry as its way of working, that’s progressive collaborative inquiry.

Progressive collaborative inquiry is not just a method — it’s a culture.

What Do We Mean by a PLC?

Different researchers emphasise different things about PLCs:

• Shirley Hord (1997, 2004): “a community of educators who work collaboratively and continually to seek and share learning, and then act on what they learn to enhance their effectiveness as professionals for the benefit of students.”

• Richard DuFour (2006): “educators committed to working collaboratively in ongoing processes of collective inquiry and action research to achieve better results for the students they serve.”

• OECD (2016): “a group of teachers who meet regularly to reflect on their practice, engage in collaborative learning, and improve their teaching with the goal of improving student learning.”

• Judith Warren Little (1990; 2003): distinguished between shallow cooperation and true interdependency.

My Working Definition

A Professional Learning Community (PLC) is not just a meeting or a program. It is a discipline of collaborative inquiry where educators:

- Work interdependently — not simply side by side, but with shared responsibility and accountability.

- Use evidence of student learning to guide their practice.

- Take collective responsibility for the success of all students.

- Engage in continuous cycles of reflection, action, and adaptation.

At its core, a PLC is a professional culture — not a calendar slot.

Why Interdependency Matters in My Research

Interdependency is the difference-maker. Teachers who simply share ideas often remain in their silos. But when they plan, trial, and reflect together — when they rely on one another to move student learning forward — their belief in their collective capacity grows.

Think of it like a neural network: one neuron firing doesn’t do much. But when connections multiply, the system learns and adapts. That’s what interdependency feels like in a PLC: the intelligence is in the connections, not the individual teacher.

Interdependency is the difference-maker.

Misconceptions That Derail PLCs

Three traps I’ve seen most often:

1. PLC as program — announced with fanfare, lived out as another meeting on the calendar. The excitement fades faster than milk in the staff fridge.

2. Over-structuring — meetings so rigid you half expect someone to say, “Objection, Your Honour!”

3. Under-structuring — the “friendly chat” version of a PLC, where you leave 45 minutes later with nothing but a doodle in your notebook and a vague craving for biscuits.

Collaborative inquiry turns meetings into learning. It’s professional learning with teeth.

The Power of Collaborative Inquiry

At their core, PLCs should run as collaborative inquiry cycles: identify a student need, frame a question, trial a strategy, gather evidence, reflect, and adapt.

For me, it’s a bit like my Garmin watch obsession (and yes, I realise my addiction to feedback is very real!). A Garmin doesn’t just tell you that you went for a run; it tells you how you ran, pace, cadence, heart rate, VO₂ max, and recovery time. It provides feedback that pushes you forward.

Collaborative inquiry is the Garmin of teacher learning. It’s precise, actionable feedback that drives improvement.

Is your PLC working like a Garmin or more like a pedometer from the 90s?

The Anatomy of a PLC (What Works in Practice)

From my experience, the anatomy of a PLC that works includes:

- Purpose. Everything comes back to student learning.

- Structure. 4–8 teachers, regular, focused time.

- Roles. Rotate facilitator, recorder, timekeeper.

- Protocols. Looking at student work, tuning protocols, data conversations.

- Inquiry Cycle. Identify → Question → Trial → Evidence → Reflect.

- Success Matrix. Impact on student learning, teacher learning, and culture.

- Leadership Alignment. Must sit inside the strategic plan, not on the margins.

A PLC without inquiry is like a gym session without sweat — you showed up, but you didn’t get stronger.

What PLCs Are Not

Sometimes it helps to clarify the shadow side:

• A PLC is not a therapy group — venting has its place, but it doesn’t shift practice. (Biscuits optional.)

• It’s not a book club — unless your book club requires action plans and student data, which frankly sounds like a terrible book club.

• It’s not a meeting about meetings — we’ve all been in those, and they should come with hazard pay.

Are your PLCs building teacher capacity, or just maintaining compliance?

Case Studies From My Experience

The Year 5 Writing Team — Interdependency in Action

I still remember sitting in on a Year 5 writing PLC. The teachers spread out drafts of student work across the table. Instead of saying, “Oh, I did this in my class and it worked,” they rolled up their sleeves and co-designed a shared mini-lesson.

The following week, every single teacher taught that same lesson. A week later, they returned with student samples. There were sticky notes, laughter, honest questions:

“Did you notice that the boys in 5C really struggled with paragraph transitions?”

“This anchor chart made a huge difference in my room — let me show you.”

This was true interdependency. Each teacher was relying on the others, not just to share, but to build something stronger together. And the impact was immediate: students wrote with more confidence across all five classes.

The Science Department That Drifted — Cooperation Without Interdependency

Then there was the science team. They were collegial, kind, and genuinely enjoyed their meetings — but week after week, the conversations circled around logistics:

“What equipment do we need for the lab?”

“Can you cover me for duty on Thursday?”

One teacher bravely brought student work, hoping to spark discussion. It was glanced at politely, then quickly moved aside. Nothing ever looped back into classrooms.

Judith Warren Little (1990, 2003) would have called this cooperation, not collaboration. They were side by side, but not interdependent.

And the impact on students? Minimal.

(It was the educational equivalent of “this meeting could have been an email.” ARGH!)

Transforming a Bilingual Team — Building Interdependency Across Cultures

Perhaps the most powerful PLC journey I’ve witnessed was with a bilingual team — English and Chinese teachers working together.

At first, there was tension. The English teachers felt the Chinese curriculum was too rigid; the Chinese teachers felt the English approach was too loose. Meetings often ended with silence, or worse, polite nodding, followed by teachers going back to their old ways.

Through deliberate use of collaborative inquiry, the team began bringing shared student samples. Together, they asked:

“How do our bilingual learners transfer skills between English and Chinese writing?”

Over time, trust grew. They discovered strategies that worked across both languages, like sentence stems and paragraph organisers. For the first time, they planned a joint unit — and when the students produced essays drawing on both English and Chinese skills, the pride in the room was palpable.

Neither side could have achieved this alone. Interdependency turned what began as conflict into convergence.

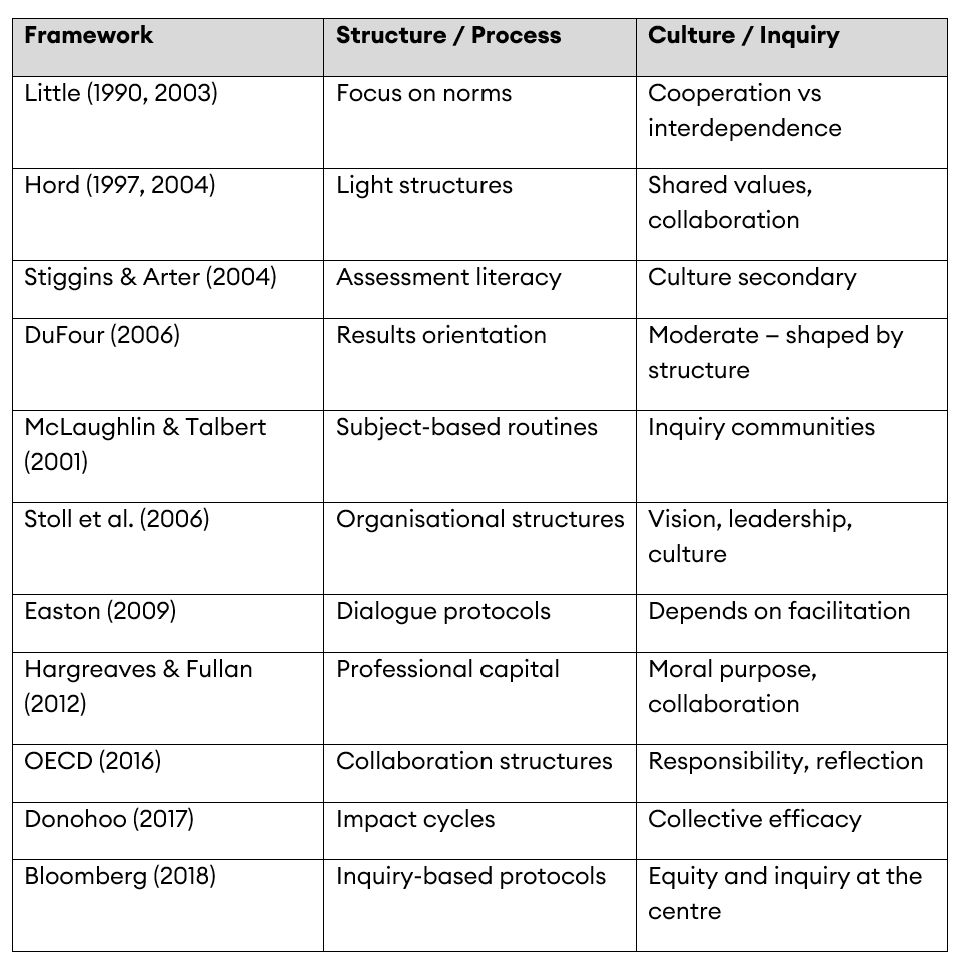

Frameworks for PLCs: A Bigger Landscape

To make sense of PLC frameworks, I think about two dimensions:

- Structure / Process (tight cycles, protocols, assessments)

- Culture / Inquiry (trust, reflection, equity, efficacy)

The most effective PLCs combine structure and culture.

A note on the Great Teaching Toolkit (Evidence-Based Education, 2020):

The GTT is not a PLC framework, but a framework for what ‘great’ teaching looks like. It fits inside PLCs as the focus of inquiry cycles:

- PLCs = the lab (the process, protocols, and culture)

- GTT = the curriculum of improvement (what teachers reflect on, test, and refine)

The GTT gives us what to improve; PLCs give us how to improve it, together.

Future of PLCs

Looking ahead, PLCs can’t remain “Thursday at 3pm” meetings. They need to evolve into professional learning ecosystems:

- Could AI analyse student work and highlight misconceptions before the PLC meets?

- Could PLCs extend across schools and even countries?

- Could PLCs become the innovation engines that prepare teachers and students for futures we can’t yet imagine?

Looking back, I’ve seen PLCs falter when treated as a program, and flourish when lived as a discipline.

PLCs are not really a “thing” to implement, but a way of thinking and working together. They’re the convergence point where structure meets culture, where collaboration meets inquiry, where teacher learning meets student growth.

I began this post by asking you to remember what it feels like to be part of an effective team. The flow, the trust, the shared responsibility. Aristotle said it best: “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” A PLC is not just teachers sitting side by side; it’s the alchemy of interdependency, where individual strengths combine into collective power, turning it into pure and precious gold. That’s the future of professional learning.

References

· Bloomberg, L. D. (2018). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research for Policy and Practice. Routledge.

· Donohoo, J. (2017). Collective Efficacy: How Educators' Beliefs Impact Student Learning. Corwin.

· DuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R., & Many, T. (2006). Learning by Doing: A Handbook for Professional Learning Communities at Work. Solution Tree.

· Easton, L. B. (2009). Protocols for Professional Learning. ASCD.

· Evidence Based Education. (2020). Great Teaching Toolkit: Evidence Review.

· Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School. Teachers College Press.

· Hord, S. M. (1997). Professional Learning Communities: Communities of Continuous Inquiry and Improvement. Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

· Hord, S. M. (2004). Learning Together, Leading Together: Changing Schools through Professional Learning Communities. Teachers College Press.

· Little, J. W. (1990). The Persistence of Privacy: Autonomy and Initiative in Teachers’ Professional Relations. Teachers College Record, 91(4), 509–536.

· Little, J. W. (2003). Inside Teacher Community: Representations of Classroom Practice. Teachers College Record, 105(6), 913–945.

· McLaughlin, M. W., & Talbert, J. E. (2001). Professional Communities and the Work of High School Teaching. University of Chicago Press.

· OECD. (2016). Supporting Teacher Professionalism: Insights from TALIS 2013. OECD Publishing.

· Stiggins, R. J., & Arter, J. A. (2004). Classroom Assessment for Student Learning. Pearson.

· Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221–258.